Reflective Practice: Thinking About Our Thinking In Action and Avoiding Functional Stupidity in War

Second part of a Two Part Series; Drawing from earlier draft work

Continuing from Part 1 located here. This is an earlier version of a chapter that eventually made its way into my second book, ‘Beyond the Pale’, which is available for free PDF download at the Air University Press website.

An example of how double-loop thinking fails an organization in complex security contexts can be found in what the United States Air Force did in Afghanistan. During the American-Afghanistan Conflict from 2001-2021, the Department of Defense decided early on that the Afghan Air Force would be trained and equipped with smaller cargo aircraft (C-27A planes) that were retrofitted and enhanced to mirror how the U.S. Air Force performs air movements and supply missions. In the first phase which ended in 2014 with catastrophic failure, all of the short-runway take-off C-27A planes were sold as scrap metal after being grounded for over two years.[1] This half billion dollar fiasco featured a single-loop cycle of the U.S. Air Force advisors in the NATO-Training Mission, Afghanistan (NTM-A) organization attempting to improve the Afghan pilot and maintenance capabilities while foreign contracted supporters ended up taking over the majority of the maintenance duties to achieve mission goals. Despite maintenance being accomplished, the Afghan Air Force remained largely untrained and entirely dependent upon foreign assistance.

The double-loop cycle that also existed within this same Afghan aviation endeavor was where the U.S. Air Force sought to find ways to restart the training of pilots and ground maintainers so that they might become independent when the Obama Administration in 2012 accelerated all transition of security missions and permanent Afghan security infrastructure over from Coalition to Afghan Security Forces. In multiple strategic planning sessions within NTM-A,[2] the U.S. Air Force leadership within NTM-A stipulated to the design and planning teams that, under no circumstances would a future Afghan Security Force restructuring proposal include any departure from the current Afghan Air Force implementation plan of the C-27A airframes through 2020 when those planes would reach the end of their service life. Anything else for the Afghan Security Forces might be modified, but for the Afghan Air Force, only the operators on either side of the ‘advisor-advised’ relationship and certain processes within the overarching strategy could be targeted.

As the Afghan Air Force would collapse well before the expected 2020 life cycle termination of the original C-27A fleet, the American and Coalition advisors were trapped in a double-loop learning cycle where mission performance was entirely oriented upon the original frame preservation. Western military aviation organizes within a highly centralized and technologically sophisticated form of tasking aviation effects with a decentralized support model; essentially ground forces will have some aviation available at all times, but they cannot specifically control or task direct support due to the entire organizational form/function of how western air forces exercise their abilities.[3]

Many air forces through World War II and even into the 1950s employed an alternative model termed ‘penny packets’ where ground forces directly controlled and employed aviation. This paired well with lower technology, simpler airframes. Why didn’t NTM-A consider implementing a ‘penny packets’ construct with low-tech, simpler airframes for the Afghan forces in 2010 when things were going so poorly? Those questions would not be considered and the strategic guidance issued from the start prevented any such inquiry from migrating away from the original goal to have the Afghan Air Force largely function as a mirror reflection of how the U.S. Air Force advisors themselves functioned. This is where ‘triple loop learning’ was absent, and likely a fundamental reason for understanding the sudden and complete collapse of the Afghan Security Forces in 2021.

Triple Loop Learning: Sensemaking beyond Institutional Limits

Flood and Romm present their version of ‘triple loop learning’ as one where synthesis of multiple frames are realized and appreciated by a triple-loop learning organization. They articulate this synthetic thinking as iterative, nonlinear, and able to paradoxically consider interior and external perspectives using a diversity of models, methods and theories that disrupt established institutional frames (what maintains single and double-loop thinking). This evokes a military paradox where the single and double-loop learning is appealing to organizations that want to be in control, whereas triple-loop learning acknowledges that in complex systems, control is usually an illusion. Ryan et al summarize this tension with: “If events are random, we are not in control, and if we are in control of events, they are not random.”[4] Mintzberg et al differentiate strategizing in complexity as a process characterized by “novelty, complexity and open-endedness… the organisation usually begins with little understanding of the decision situation it faces or the route to its solution.”[5]

However, Flood and Romm’s position is weakened by a lack of clarity of what constitutes triple-loop from a philosophical, theoretical and multidisciplinary frame of reference. To enhance their argument, the theories of Donald Schön, Karl Weick and other influential sociologists are merged here, along with complexity theorists that also engage on what a ‘reflective practitioner’ is for the socially complex reality that humans generate atop the existing natural order of complexity. Schön uses ‘reflective practice’ while Weick opts for ‘sensemaking’, yet these concepts overlap and interplay extensively in this presentation of ‘triple loop learning’ as presented in this article.

A primary oversight of single and double-loop thinking is the emphasis on processing all activities through a lens of rational action. Once the norms found to be most compatible with rationalized action are identified- efficiency, consistency, uniformity, repetition, coordination- the entire decision-making process (from strategic to tactical) is appraised entirely upon how tightly these norms are followed. Wildavsky elaborates with:

The assumption is that following these norms leads to better decisions. Defining planning as applied rationality focuses attention on adherence to universal norms rather than on the consequences of acting one way instead of another. Attention is directed to the internal qualities of the decisions and not to their external effects.[6]

Within non-reflective thinking, strategists and planners are trapped into this rationalized action frame, and due to this often unwitting rationalization that planners conduct while moving in a single or double-loop, the organization fails without realizing why it is failing. In rationalized planning, “planning is the attempt to control the consequences of our actions… planning is the ability to control the future by current acts,” yet a single loop cycle of “planning becomes a self-protecting hypothesis; so long as planners try to plan, it cannot be falsified”[7] in that when planning outcomes do not match the original intent, planners can offer that “the enemy has a vote” and that the planning process itself was a proper rationalization despite execution failures and surprises. The inability to break out of these self-referential patterns will protect the rationalization of what constitutes a valid planning process, while mitigating process errors by blaming either the operator and/or a complex external system. As long as planners plan by the preferred rationalized process, the institution preserves itself inside a non-reflective cycle of thought and action.

Yet this sort of rationalization may work in simple and some complicated systems (cite Snowden), yet they become paradoxical in complex (and chaotic) systems where warfare occurs. Single and double loop cycles steer operators toward assumptions that their institution has already worked out the rationale employed, so that by using the linear, mechanistic decision-making methodologies in military doctrine and adhering to the rules therein, the entire process subscribes to the rationalized action. Yet complexity violates this as “what is rational to the values of the actor may be different to the organisational values, which in turn may be different to the values highlighted by the subsequent analyst.”[8] Triple loop thinking demands reflective practice so that operators can think paradoxically, explore these tensions in how humans do interpret reality in strikingly different ways yet are systemically acting within the same dynamic, complex and emergent system that rejects much of the logical conclusions that single and double-loop thinking can provide. Strategies in complex contexts may form gradually as the operators interact and sensemake, even unintentionally or in highly unexpected, emergent ways.[9] This runs contrary to single and double-loop assumptions of control and prediction.

Schön and Rein see reflective practice as the intertwining of thought and action, but not in the linear-causal form that single and double-loop operators frame reality. In those situations, “practitioners tend to assume that the factors essential to the goals they pursue lie at least partly within their control. With their taken-for-granted assumptions, they tend to ignore the factors that lie beyond their control and the shifts of context that may distort the hoped-for outcomes of deliberate action.”[10] The belief that a system is stable and understandable enough to permit systematic logic with future goals reverse-engineered along linear-causal ‘lines of effort’ reinforces this assumption. Yet complexity regularly violates these aspirations of reductionist, mechanistic control. Humans are not objective creatures, nor does the social construction of human experiences permit some universal order and stability so that one context can transfer to another and yield similar, repeatable results. Instead, it is the social framings held by actors that need to be added to systemic appreciation.

Danielsson, using the alternative spelling of ‘reflexivity’[11] frames the rise of reflective practice in military organizations with: “Reflexivity shifts the military attention to the knowing subject, to the social conditions and constitutions of knowledge, and to the interactions between the knowing subject, knowledge constructions, and other objects and subjects in the world.”[12] Danielsson, in studying the emergence of reflective practice across military organizations observes that this multi-disciplinary approach has entered into military education, “often in close association with the broader discourse on military design…and not without resistance.”[13] Whether triple loop learning and overlapping concepts of reflective practice and sensemaking are indeed gaining headway into traditional military decision-making methodologies, doctrine, education and training remains questionable, as numerous educators, theorists and facilitators write about the difficulty and resistance in getting these ideas and perspectives past the institutional gate keepers and defenders (witting and unwitting) of single and double-loop thinking orthodoxies.[14]Reflective thinking is unavoidably disruptive, thus any significant military resistance indicates that triple loop learning as a novel process is creating the desired effects upon an organization rooted in single and double-loop practices.

Schön and Rein elaborate on reflective practice with: “the frames held by the actors [are what] determine what they see as being in their interests and, therefore, what interests they perceive as conflicting. Their problem formulations and preferred solutions are grounded in different problem-setting stories rooted in different frames that may rest, in turn, on different generative metaphors”[15] While single and double-loop learners implicitly accept their assumptions without any critical inquiry into the larger system, reflective practitioners follow a third loop of learning where they accept that “there are no objective observers. There is no way of perceiving and making sense of social reality except through a frame, for the very task of making sense of complex, information-rich situations requires an operation of selectivity and organization, which is what “framing” means.”[16] Reflective practitioners move to higher levels of abstraction and inquiry to illuminate the institutionalized processes and the ontological as well as epistemological choices that stimulate such structures in a frame. WHY folds back upon WHY, with recursive iterations of deeper introspection beyond the limits of causal single and double-loop thinking. Tsoukas distinguishes reflective practice from non-reflective practice (those trapped in single or double loops) with:

We become reflective practitioners when we both unreflectively carry out our research tasks to generate new knowledge about organizational phenomena of interest and engage in discussions about the validity of our knowledge claims.[17]

Reflective practice demands the acknowledgement that paradox and complexity are not just foundational to reality- they should be readily embraced instead of marginalized or avoided. Tsoukas offers: “The human world cannot be mathematized because it is a world defined by beings with the capacity to reflect upon, and so contradict, any mathematical description made of them.”[18] Militaries confuse the second order of complexity (that which humans socially construct) with the patterns and conditions of the first natural order of complexity. This leads to a highly engineered, formulaic, and Newtonian Styled mode of systematically framing reality- one that becomes preferential to single-loop and double-loop cycles of theory and practice for an organization.[19] Militaries contradict Tsoukas and invest significant mental energies in planning and strategy-making by attempting to mathematize warfare entirely, to include the human actors on both sides of a conflict. They attempt to understand war as a biological or physical fact of reality, when instead it is a socially created one.[20] The Western world has incorporated complexity theory writ large, yet militaries appear devoted to their Newtonian Styled war frame which in turn cannibalizes complexity concepts so that the meaning is lost, and orthodox planning doctrine becomes littered with “faddish new fashions” devoid of content.[21]

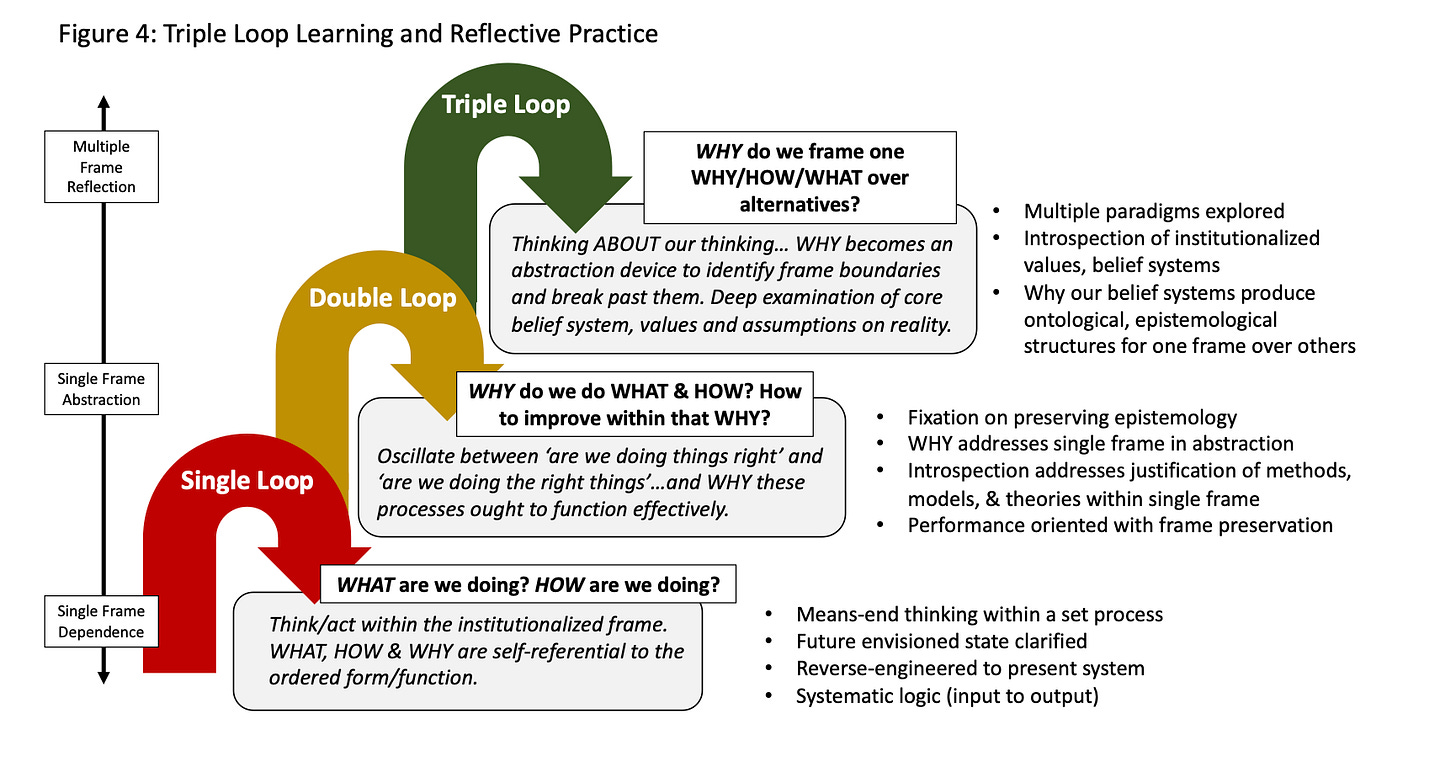

In the illustration below, the triple loop exists only at the highest level of abstraction, beyond the self-imposed limits of any single paradigm (organizational frame). This level of inquiry and awareness does not look at theory from a theoretical level, but advances to a higher level of epistemological inquiry that Tsoukas terms the meta-theoretical level.[22] At this meta-level, the operator questions beyond a single frame and becomes appreciative about multiple social paradigms, and instead of attempting to generate a single theory about a particular topic, one attempts to “make the generation of theory itself an object of analysis.”[23] As opposed to generating superior results through increased analysis and descriptive knowledge that attempts to reduce complexity mechanistically into smaller isolated pieces, reflective practice thinks systemically where “actors become aware of the assumptions, the presuppositions, and the point of their actions only after they have obtained some distance from their actions, by looking back at them. Greater awareness comes about when we reflect on the way we reflect.”[24]

For military organizations conducting a ‘post-mortem’ of the spectacular and unexpected Afghan military collapse in 2021, those engaging in a second-loop non-reflective practice might seek to redefine existing methods for counterinsurgency operations or how to better accomplish foreign internal defense activities by introducing a new theory, new models and different terminology to buttress the existing decision-making methodology. However, triple-loop operators would deconstruct why modern militaries emphasize systematic logic for executing warfighter activities, or why they also project their own institutional values and organizational structure upon all foreign entities regardless of context. Reflective practitioners might explore the dissimilar war paradigm of the adversary as well as why modern militaries dismiss such things as irrelevant to universal war principles they employ to understand and define the enemy, or why modern militaries converge decision-making through reverse-engineered, ends-ways-means derived formulas that violate most tenets of complex systems. In the triple loop, operators are thinking about their own thinking, and recursively using WHY oriented inquires to explore well outside the institutionalized processes of linear-casual, systematic sequences nested to preconceived goals.

Entering into triple loop learning and reflective practice swings critical self-inquiry not just toward one’s processes and institutional biases, but into abstraction on how and why humans socially construct a rich, dynamic tapestry of ideas, belief systems, values and language upon a naturally complex world. Performing reflective practice requires the operator to construct narratives iteratively as they attempt to appreciate what ultimately is an interpretivist reality. This third loop of systemic inquiry features recursiveness, in that as one engages with the system under study, “we must also confront our own complexity, in narrative terms… reflexivity is related to contextuality in the sense that inclusion of the narrator in the narrative involves another layer of context.”[25] This generates recursiveness where reflective inquiry reveals layer after layer of systemically arranged and intertwined constructs. In triple loop thinking about complex systems, ‘meaning’ outpaces ‘predetermined goals’ for how organizations ought to approach decision-making.[26] This is devastating for single and double-loop thinkers that insist upon goals/ENDS for any and all planning endeavors, as they are stuck in non-reflexivity.

Tsoukas and Hatch elaborate on ‘recursiveness’ with: “The recursiveness of context extends to the recursiveness of narrative thinking, so that thinker and thought become so intertwined as to render the possibility of disentanglement unimaginable, and ourselves more complex.”[27] The preferred single or double-loop approach of modern military decision-making methodologies such as the Joint Planning Process simply are ill-equipped to do anything other than mechanistically isolate, categorize, and in mechanistic, systematic fashion apply universal formulas toward a complexity that must reject such attempts outright. Schön’s position on reflective practice holds that “the problems of the real world practice require a process that engaged the practitioner’s theoretical, procedural, and reflective knowledge.”[28] In this triple loop as illustrated in the above graphic, decision makers must “move beyond a purely rational model of understanding to one that is transactional, open-ended, and inherently social.[29]

[Draft Chapter] Conclusions:

Modern militaries rely on single and double-loop thinking processes in order to maintain a fragile decision-making framework that is hierarchical and scales upward or downward with the same constructs intact. Everything to be planned for future action revolves around an institutional fetish for clear, objective and stable goals/ends… despite the paradoxical admission that all war is wickedly complex and resistant to such efforts. “The military mind exhibits an almost pathological desire to achieve certainty.”[30] Meiser concludes that: “the American way of strategy is the practice of means-based planning: avoid critical and creative thinking and instead focus on aligning resources with goals… [the] problem with our current understanding of strategy are exacerbated by the whole-of-government approach encouraging us to define national power as a discrete set of instruments that form a convenient acronym.”[31] This is an expression of single and double-loop learning, where militaries become trapped in cycling through a process that prohibits any systematic appreciation beyond the institutionally imposed rationalization that process improvement is only possible through tighter adherence and compliance. Organizations are educated, trained and evaluated in training centers to follow the process, refer to doctrine, and self-assess entirely on how well they achieved process compliance as a linear-causal assumption that proper process leads to goal accomplishment.

The ‘ENDS-WAYS-MEANS’ structure operates at a high strategic level and also scales down in subordinate fashion to the smallest tactical or technical activity if properly rationalized and sequenced within the bigger frame. Much as Russian nesting dolls fit within each other, militaries assume that the formulaic, universal and repeatable qualities of isolated tactical events in warfare must correspond directly with broad, strategic and operational processes so that planners at all levels can synchronize and accomplish desired goals. This reflects a Newtonian styled perspective upon warfare, and violates most core tenets of complexity theory and how humans collectively socially construct a second order of reality upon an already complex natural order. An example of this dominant mindset is illustrated below using a Joint Publication 5-0, Joint Planning popular graphic.

(graphic above located at: https://www.usmcu.edu/Outreach/Marine-Corps-University-Press/Expeditions-with-MCUP-digital-journal/The-Operational-Warfare-Revolution/)

Ramaprasad and Mitroff, in their paper ‘On Formulating Strategic Problems’ observe that “a strategic problem does not have a unique, universal formulation. Second, formulating a strategic problem in different ways can result in different solutions to the same problem. Third, an error in formulating a strategic problem can result in solving the wrong problem.”[32] Lastly, non-reflective practitioners cannot break out of this loop, dooming the organization to cycling back through where one might be effectively ‘solving’ certain problems at a tactical level, that success is localized exclusively to one potentially irrelevant part of a larger system where the strategy is entirely decoupled from the tactical activities. This is ultimately why strategists and planners in military organizations must gain reflective practice and assume a triple-loop learning approach.

Triple-loop learning incorporates reflective practice so that strategists and planners can break out of institutional barriers and single-frame limitations. Reflective practice involves what Wieck also terms ‘sensemaking’ where there is “the process of social construction that occurs when discrepant cues interrupt individuals’ ongoing activity, and involves the retrospective development of plausible meanings that rationalize what people are doing.”[33] Triple-loop learning is already found in many of the military design methodologies, particularly those drawing from the theoretical work of Shimon Naveh, Ofra Graicer and the Israeli Defense Forces. [34] Reflective practice can be located in recent design case studies such as in the 75th Ranger Regiment, Canadian military efforts, Australian endeavors, in NATO, and across American services. [35]

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sapiens, Technology, and Conflict: Ben Zweibelson's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.