On Empathy and Multiple Stakeholders: The Rise of Human-Centered Design

Third entry in this series using an earlier unpublished design chapter I wrote several years ago. Links to Part 1 and Part 2 below.

Digging through my hard drives full of various writing projects over the last 15 years, I stumbled upon this large unpublished design chapter. Parts of it ended up influencing my first book, ‘Understanding the Military Design Movement’ (located here on Amazon), while other efforts such as several Springer Military Strategy chapters inherited portions. Regardless, I have not shared this version previously and will paste it below. This chapter is over 21k word count (45 pages), so we will need to post this in a 4-part series. Part 1 is here if you missed it. Part 2 is here.

Part 3:

By the late 1950s, various industrial design methods within a range of commercial disciplines would begin encountering challenges that relate to rather subjective topics that did not appear ‘solvable’ using objective, analytic processes alone. Dynamic and complex systems featured a ‘messiness’ or sophistication that prevented any solution from working,[1] and often featuring a ‘wickedness’ that denied previous solution frames from being reapplied to future ones.[2] Often, the best optimized industrialized solutions would meet all design requirements, yet unexpectantly fail in unforeseen ways when applied to the real world. Unexpected perspectives, groups of marginalized or ignored stakeholders, and unanticipated second and third-order effects created chaos out of the best applied design efforts. This reflected an ever-increasingly sophisticated world where information, technology, cultures and ideas could change how humans made sense of reality and acted within it. White’s postmodern study of ‘content’ and ‘form’ and how people construct narratives even while attempting to remain entirely objective provides significant insight here.[3] The analytic optimization of industrialized design methods could only deliver so much before breaking down. This seeming irrational quality and dynamic, ever-changing complex context demanded alternative ways to think about human thought and action to include designing for those needs.

The ability to empathize with others and provide user experiences and design complex projects where multiple stakeholders held paradoxical needs and views would spawn the need for a new way of designing.[4] Human-centric design would rise up out of the flaws and lack of empathy and societal consideration of the first design movement. In the mid-twentieth century, the foundations of this second design wave[5] would be established by design theorists such as Horst Rittel, Victor Papanek, Bruno Munari, and Melvin Webber moving against the ‘design science’ constructs contributed by the analytic-oriented design theory proposed by Bruce Archer and Herbert Simon.[6] The former wanted to increase the awareness of humans within the design process and design context, while the latter sought to marginalize or even eliminate human volatility from what could be a more efficient and stable design logic. In the human-centered design applications, ‘design’ is an innovative, highly creative, and cross-disciplinary tool[7] that differs significantly with positivist based military analytic decision-making methodologies that the post-WW2 militaries of the same period would continue to hold to.

Although outside the scope of this research, the different epistemological and methodological positions of Simon, Archer, Rittel, Webber, and Papanek demonstrate the increasingly sophisticated and multidisciplinary scope of design for complex, dynamic contexts. Essentially, Rittel in the late 1950s pioneered much of the theoretical and educational groundwork for human-centered design despite many of his lectures not being published publicly until 2010,[8] Simon and to a lesser extent Archer shaped the meta-discussions on the orientation of design as a practice[9]in the 1960s. Although Simon was a pioneer in framing design as a distinct discipline, he is criticized of taking a positivist approach and rendering design as an engineering rationalization that sought objectivity over subjectivity;[10]this would create subsequent design introspection later on the topic of ‘empathy’ that his work would lack. As Krippendorff critiques, “[Simon’s] positivism led to what we now recognize as a universalist epistemology which is no longer suitable in information-rich environments such as ours.[11] Rittel similarly criticized a purely positivist approach within science as insufficient in designing for action in complex reality. Archer promoted a rationalized ‘science of design’ thesis using mathematical equations and geometric graphics to isolate design from artistry, moving closer to Simon’s orbit and attempting to render the subjective qualities of design artistry as also reducible to scientific measurements and procedures.[12]

Regardless, Simon’s pioneering work influenced many subsequent design efforts in the 1970s-80s, and critical theorists such as Papanek disrupted and dismantled cherished design beliefs of the commercial practices and capitalistic constructs to advocate alternatives.[13] By the early 2000s, Krippendorff advocated for a philosophy doctorate for design, and the core argument that “design must continuously redesign its discourse and itself.”[14] He would advocate that designers apply their design principles also to themselves, indicating that even the current popular design methodologies across the commercial design world were temporary and needing to be challenged, deconstructed, and replaced with novel, emergent forms of design.

Sociologist Tsoukas reinforces this on promoting a dialogical approach to the creation of new knowledge. “Novel combinations create new categories to describe or bring about changes in something familiar…the new concept may have emergent attributes, that is, attributes that are different from those of either of the constituent parts.”[15]Tsoukas, Schön and Krippendorff (each drawing from organizational theory or philosophy) emphasize the important of ‘thinking about thinking’ in order to disrupt one’s own frame, break through set epistemological choices by realizing and then stepping beyond them.[16] Krippendorff would advocate for an epistemologically informed ‘philosophy of design’ that acknowledges differing design paradigms as well as the perpetual transformative nature of design practice itself.[17]

Human-centered design broadly addresses the prominence of human perspective within the design methodology of bringing organizations and individuals the innovation that is needed but does not yet exist. The first designer to describe design in this sense was Buchanan with: “the problem for designers is to conceive and plan what does not yet exist, and this occurs in the context of the indeterminacy of wicked problems, before the final result is known.”[18]Buchanan appears to be modifying early design theory on wicked problems as first created by Rittel in the 1950s-1960s,[19] as well as possibly some early ‘science of design’ theory proposed by Archer.

Archer, while advocating a positivist orientation on design, emphasizes the “element of innovation is always present in design” while describing the overall purpose of design activities relates to the planned production of something (product, user experience) or to be fashioned with artistic skill; mere description of existing and known artifacts is not an act of design for Archer. It must have “at least a modicum of originality.”[20] Later, designers Nelson and Stolterman would promote a similar design definition echoing Buchanan’s theme,[21] and military designers Naveh and Graicer provide similar phrasing in their overarching approach in military applications covered in the next chapter.[22] Problems in human-centered design are framed within complexity where the users must be deeply considered, design is done holistically, and purely analytic approaches devoid of synthesis and extensive theoretical development will be entirely insufficient and potentially hazardous. [23]

Whereas industrial design relies heavily upon analytic optimization towards greater efficiencies and developments,[24] human-centered design focuses on the irrational, subjective, and often nonlinear aspects of humanity[25] that industrial design methods routinely marginalize or seek simple majorities to streamline. Design models emerge out of experimentation with complexity theory, new organizational concepts, as well as non-western cultural traditions and patterns.[26] The first wave of industrialization designed towards centralized control, the rise of bureaucratic organization, and standardization[27] that quickly became favorites of militaries yet problematic for designers seeking customization.

Empathy-based design methodologies first emerged in the early 1960s and quickly became mainstream in various design fields as well as across design academia by the 1980s. [28] Human-centered design, as a meta-design mindset, recognized that the strengths of industrial design’s ability to optimize, engineer, and accelerate efficiency gains could frequently miss the mark and result in well-designed products failing. That failure was not necessarily due to flaws in the design output although certainly many new products were defective or poorly designed. Rather, designers by the mid-twentieth century began to appreciate that some things could be designed strictly within an industrial methodology that did not consider or explore vital systemic tensions or minority perspectives.[29] Krippendorff, in critiquing the early over-engineering emphasis of design theory such as Simon’s, saw the reason of design product failures as part of the emphasis on a centralized hierarchical mode of industrialized design:

Simon came to celebrate hierarchy and the kind of mono-logical rationality that is typically pursued in the design of highly functional products. In the human use of artifacts, the application of this techno-logic creates the need of forcing diversity into common frameworks, applying uniform standards on subordinates by a central authority, a government, a leading industry- including by “ingenious” designers…Simon could not anticipate the trajectory of artificiality we seem to be pursuing. He could not experience that hierarchical systems of some complexity hardly survive in democratic, market-oriented, and user-driven cultures…Design tasks involving teams or stakeholders can no longer be organized hierarchically. Although traditional designers might decry the loss of control that hierarchies provided, chaos, heterarchy, diversity, and dialogue are the new virtues that design must embrace today.[30]

Analytic optimization and improved efficiencies without subjective or even irrational qualities that involve human emotion, curiosity, amusement and other non-objective constructs were not just relevant but essential. This tension is explained by Krippendorff in that a purely engineering mindset or discourse will rationalize reality and attempt to ‘solve’ problems by optimizing techniques and search for strategic approaches to achieve predetermined ‘ends.’ This highly industrialized mode of designing through analytical science creates a reality that precludes the best qualities of design. “Science inquires into what is, design into what could be.”[31] Attempts to remove subjectivity and empathy from any design methodology may instead purge any design opportunity from it, and subsequently delivering a well-engineered but useless outcome. The very qualities that earlier industrial designers had attempted to marginalize or eliminate entirely from manufacturing and production processes apparently were instead critical to the notions of creative destruction, innovation, exploration and opportunity in human design.[32]

This paradox meant that in complex systems, sometimes the inferior VHS tape would outsell the superior Beta-Max, or the construction of well-designed low-income housing would need to be torn down decades before their forecasted expiration date due to the failure of the city design to facilitate enough low-income citizens to seek to live in them. Some automobiles that perform better than competitors are nonetheless unable to sell as well as their rivals or are otherwise pushed out of the market by inferior competitors able to market in unexpected ways. Moving from the commercial design disciplines to military ones, late twentieth-century western military forces struggled with the paradox of high technology, well-funded professional militaries losing the strategic advantage to dramatically inferior funded and equipped adversaries in Vietnam, Somalia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Africa, and elsewhere.

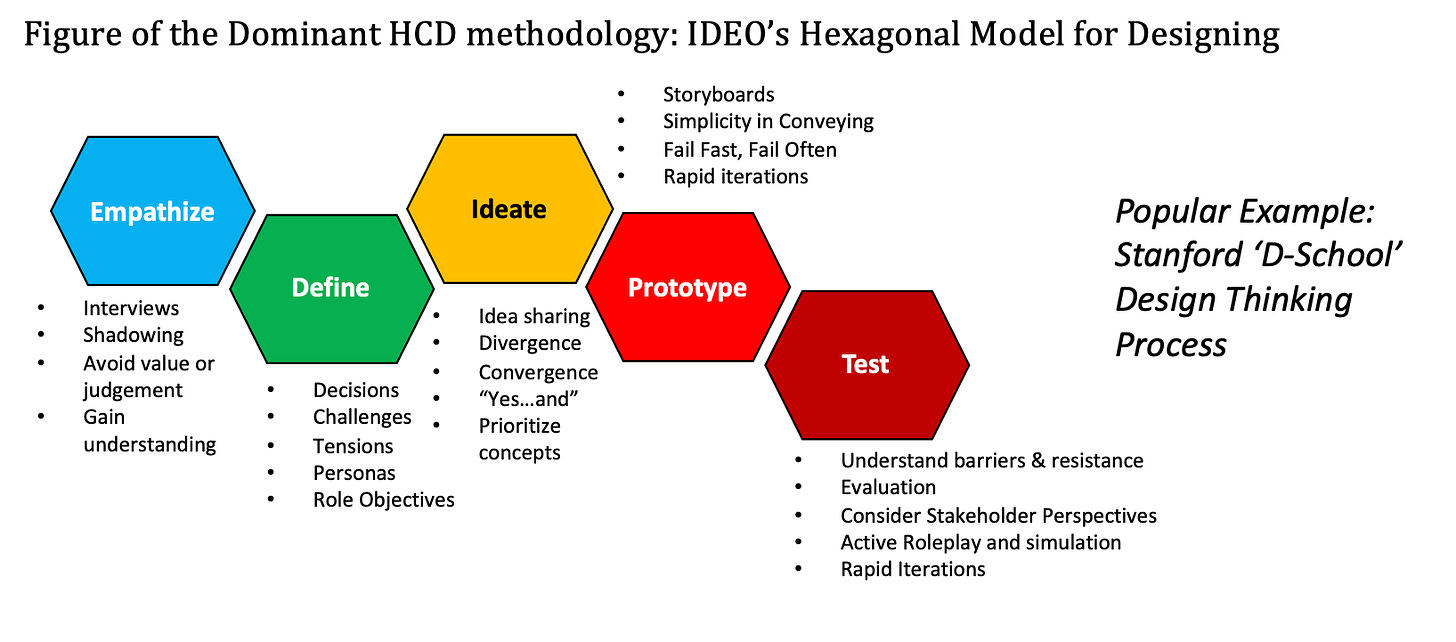

By the 1970s, formal civilian design schools existed touting various methodologies as well as entire disciplines for different design applications. In the 1980s and 1990s, multiple academic programs stood up and significant research on different design approaches occurred across various disciplines, fields, and human endeavors. Jackson provides a useful summary of this commercialization of a human-centered design process where companies such as IDEO popularized the method depicted in the figure below:

Teaching of design thinking methods have proliferated within higher education institutions since the mid-1990s, accompanied by a revival of its processual aspects. This revival was triggered by Richard Buchanan’s influential 1992 article Wicked Problems in Design Thinking which broadened the focus of private-sector design from product to service design. Buchanan also substantially developed a two-tiered process of problem definition and problem solution that had been advocated by various earlier design thinkers, [popularizing] this approach to the point where it has since become central to the design methodologies taught by most civilian higher education institutions. These methodologies include participatory design, user-centered design, interaction design, transformation design and service design…to give merely a few examples. While their details differ, each of these design methodologies includes a problem defining (also called problem framing) component and a [problem-solving] component.[33]

After the success of private-sector efforts to standardize and monetize a human-centered design sequence, universities such as Stanford developed their own education programs such as the ‘d.school’ that would teach design with an emphasis on sociological components previously ignored by earlier commercial design constructs. IDEO in particular has packaged design thinking in a profit-oriented and highly compressed educational package where students can attend short workshops of several days to learn their design methodology. Critics of this compressed format include ethnographers and complexity theorists that reject the notion of a two-day workshop in design being useful in accomplishing the deep cultural study for truly complex challenges beyond superficial or topical design requirements. One critic of IDEO’s methods and a competitor in the same market is complexity theorist Snowden, creator of the ‘Cynefin Model’[34] and a proponent of deep ethnographic studies relying on meta-data and design software:

Design thinking and ethnography has become terribly linear and terribly modified in the last couple of years. It is now being rolled out by IDEO as a series of two-day courses with certificates. When people get into two-day courses and certificates, it is the ‘end of days’ for novelty and ethnography. What happens here is the expert does the interviews and they call it ethnography. Now real ethnography is deep emersion for years or months in a situation, and you don’t see that from IDEO.[35]

While some critics challenge the brevity of the IDEO approach as well as the overly commercialized context for design education, the model itself has been for two decades the most popular and likely most utilized human-centered design methodology in commercial, civilian and even select governmental and military sectors.[36] There are hundreds if not thousands of variations on the IDEO original ‘hexagonal’ design methodology across various commercial design disciplines today. The original modes developed are depicted in the below figure and are an iterative sequence commencing with ‘empathize’, then ‘define’, followed by ‘ideate’, and then ‘prototype’ that leads to ‘test’.

The core human-centered design methodology starts with ‘empathy’ including extensive interviews, appreciation and considering alternative perspectives. Thus, the designer needs to frame various tensions concerning key stakeholders including the consumer, the producer, and also those within the system that may influence either of those groups. In the epistemological map below the methodology in the figure above, ‘empathy’ is expressed as either the exploration of multiple paradigms or possibly projecting a single dominant paradigm upon all other stakeholders. This occurs when a designer frames their ‘empathy’ so that their personal or cultural values are displaced onto actors that do not share similar ones, resulting in misunderstood or irrelevant empathetic frames. The pursuit of designing with multiple paradigms is an important feature of modern commercial as well as some (but not all) military design methodologies. Krippendorff provides an excellent summary with:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sapiens, Technology, and Conflict: Ben Zweibelson's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.